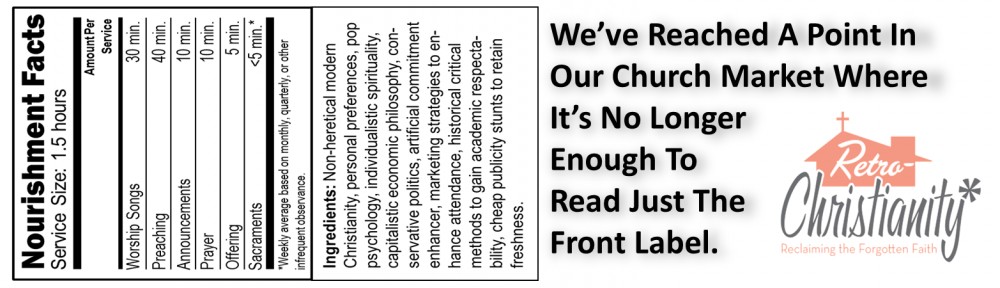

In our culture of competing churches, lackluster commitments, and consumer-driven spirituality, the idea of local church membership has suffered greatly. The classic biblical concept of a family’s covenant commitment to a definable body of believers under ordained leadership with a common calling and mutual concern has consequently been treated with skepticism, disbelief, or even contempt. This kind of cavalier treatment of the local church reflects the low commitments we see throughout our culture as marriage vows are shattered, contracts are breached, and promises are broken. However, just as Christians are called to affirm their marriage vows, fulfill their contracts, and keep their promises, we are also expected to fulfill the covenant commitment we make when we publicly join in membership to a local church.

But what do we mean by “covenant commitment” and how does this affect our understanding of local church membership? The term “covenant” simply means “formal agreement,” “solemn promise,” or “public commitment.” This relates to church membership in two important ways. First, when we describe church membership as a “covenant commitment” to a local community of believers, we are simply saying that by becoming a member of a particular church, we are not simply entering into rights and privileges, but we are assuming certain responsibilities and obligations. Second, a “covenant commitment” is more than simply being committed. I may be committed to abstain from coffee for a week (a purely hypothetical concept, of course!). However, such a commitment becomes a covenant commitment when I publicly confess my commitment before others as a formal promise or solemn vow. In the same way, regular attenders at a church may be “committed” to showing up week after week. But those who have formally entered into membership have made a “covenant commitment” when they publicly affirmed their loyalty to carry out their biblical responsibilities as members of a local body of believers.

With the general concept of “covenant commitment” defined, let’s look at a few important considerations related to the concept of church membership in the New Testament and why our official entrance into such membership must be viewed as a covenant commitment to a local, definable body of believers.

Cleaving to the Local Community

When we become members of a local church, we “cleave” to that community with the same kind of solemnity with which we cleave to our spouses or our families.

In Matthew 19:5, the Greek verb kollavw (kollao), refers to the joining in covenant commitment between a husband and wife. Elsewhere it means to enter into a contractual labor agreement, to “hire oneself out” to a master (Luke 15:15). In fact, so close is the relationship described by “cleaving” (kollao), that the term is used to describe the eternal relationship believers have when they join themselves to the Lord (1 Cor. 6:17)!

In its ecclesiastical usage, kollao is used with reference to “joining” a local assembly, even if one is already a baptized member of the universal body of Christ. Thus, when Paul traveled to Jerusalem after his miraculous conversion, he “attempted to join (kollao) the disciples” (Acts 9:26). After the church in Jerusalem responded with skepticism, doubting the genuineness of his conversion, Barnabas vouched for Paul before the local leadership of that church, that is, the apostles (Acts 9:27). From that point on, Paul’s relationship is described as “with them,” that is, a member of that community under the headship of the leadership.

Later, as Paul preached the gospel and made disciples, they “joined (kollaomai) him and believed” (Acts 17:34). We know from numerous passages throughout the book of Acts that believing and being baptized were closely associated (Acts 18:8), and that baptism itself was the first step in the life of discipleship (Matt. 28:19). We also know that discipleship involves a formal relationship of master and disciple (2 Pet 3:16). Thus, the idea of officially “joining” or “cleaving” to a particular local congregation of the body of Christ under ordained leadership for the purpose of mutual edification and accountability is quite biblical.

Accountability within the Community

Being a cleaving member of a local church involves an accountability relationship to that particular community that one does not have with any other congregation. This relationship of accountability defines who is “in” the community and who is “out.”

In 1 Corinthians 5:2, Paul commands the local church in Corinth to gather together and remove the unrepentant believer from “among” the church (1 Cor. 5:2). This has come after a proper process of church discipline. Such a removal from “among” the church is only possible if there were clearly-established boundaries of the local community. Just as a company can only fire those who are officially and legally employed, churches can only exercise discipline against those who are officially and covenantally incorporated into membership.

But can we be sure that Paul had in mind a well-defined covenanted community of actual identifiable members? Yes. In fact, in 1 Corinthians 5:13, Paul quotes a phrase from the Old Testament that clearly indicates this: “Purge the evil person from among you” (Deut. 17:7, 12; 21:21; 22:21, 22, 24). The Old Testament background illuminates Paul’s intention here. Only those who were covenanted members of Israel were responsible to its laws and therefore accountable to its discipline. That is, those who were circumcised as the sign of the Old Covenant were accountable to keep the whole Law (Gal. 5:3). In the same way, Paul regarded as accountable members those baptized believers who were covenanted to the local community in association with their brothers and sisters in the congregation under ordained leadership.

In Matthew 18, Jesus outlines a process of church discipline that begins with a private confrontation between one brother and another (Matt. 18:15). If this step fails, the next stage is to bring two or three witnesses (18:16). If this intermediate step does not bring about repentance of the transgressor, the final stage is to take the matter before “the church” (Matt. 18:17), which includes at least the leadership of the church and those who constitute the “assembly” of covenanted believers joined to that local body, accountable to its discipline. Failure to bring about reconciliation at this point leads to an ejection of that member from the local church, as described in 1 Corinthians 5:2 and 13.

Simply put, without a covenanted submission of believers to one another and to the established leadership, the kind of church discipline described by Jesus and the apostles is simply impossible. Without membership in a community, there could be no ejection from the community. And without a covenant commitment to the community, there could be no charge of a breach of that covenant with the appropriate repercussions that accompany it.

Leadership and Membership in the Community

The fact that leaders are exhorted to take care of the members of their churches demonstrates that they have a God-given responsibility for a particular definable covenant community. Without such a covenant, leaders could not responsibility and legitimately exercise such authority.

In Acts 20:28, Paul addresses the elders from the individual local church in Ephesus with the following charge of pastoral responsibility: “Pay careful attention to yourselves and to all the flock, in which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers, to care for the church of God which he obtained with his own blood.” For such a charge to have any meaning, the leadership would need to be able to identify those who are members of “the flock.” Keeping in mind that Paul is addressing the local church leadership from Ephesus, those leaders would know who was within the scope of their oversight. This “flock” is called the “church,” that is, the local congregation in Ephesus.

The apostle Peter also echoes this same kind of charge in 1 Peter 5:1–3. The elders in the churches were charged with the responsibility of shepherding (or “pastoring”) “the flock of God,” that is, an identifiable group of individuals for which the leaders were responsible (1 Pet. 5:2). In verse 3, those for whom the elders were responsible are referred to as “those in your charge” (kleros). The term is used with reference to an official, set membership in Acts 1:17, 26; 26:18. Thus, the idea of defined leadership responsibility requires defined membership boundaries and a covenanted relationship of responsibility.

The establishment of local church leadership began already in the church in Jerusalem, where the apostles themselves served as elders alongside other elders appointed in the Jerusalem church (Acts 8:1; 9:27; 11:30; 15:2, 4, 6, 22; 1 Pet. 5:1). The establishment of leadership in local churches continued in Paul’s apostolic ministry. During their first missionary journey, Paul and Barnabas “appointed elders” in every church (Acts 14:23). These elders were responsible for overseeing the community of disciples they made in each location (14:21). The fact that these members of the local church are called “disciples” is significant, as “disciple” indicated a person who was in a formal mentoring relationship. In the case of the local church community, a disciple would be in a relationship of submission to the teaching, training, and mentoring of the apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors, and teachers (Eph. 4:11). After the ministry of the apostles, the establishment of ordained leadership in each local church was intended to continue. Paul instructed Titus to “appoint elders in every town” (Titus 1:5).

The responsibility of the membership of the local church was to live in a relationship of mutual encouragement and support, meeting together consistently (Heb. 10:23). This membership in the local established church also involved a relationship of submission to leadership (Heb. 13:17).

The Seriousness of the Covenant Commitment

When a person joins a local church community with an established leadership structure and a set membership roster, they are committing to fulfill the biblical calling to that particular family of God. This commitment before God and His people is solemn and serious. It should not be entered into hastily or flippantly, nor should the church leadership and membership accept new members without scrutiny.

Scripture is quite explicit about the seriousness of our commitments as Christians—especially our commitment to build up our local church body. In general, we are to take our human commitments with utmost seriousness. In Galatians 3:15, Paul explained that “even with a man-made covenant, no one annuls it or adds to it once it has been ratified.” Thus, entering into contracts, covenants, agreements, and promises is serious. As much as it lies within us, we are to keep our commitments without wavering. Paul wrote, “Do I make my plans according to the flesh, ready to say ‘Yes, yes’ and ‘No, no’ at the same time?” (2 Cor. 1:17). Obviously, the answer is, “As surely as God is faithful, our word to you has not been Yes and No.” That is, just as God keeps His promises and covenants with us, we are to keep our promises and covenants with each other (2 Cor. 1:20).

Our reputations as consistent promise-keepers should be such that worldly flakiness and waffling are unheard of among us. This means fulfilling informal agreements, contractual obligations, and covenant commitments. In fact, rather than having to swear oaths by God, the Bible, or our mother’s graves, Christians should have such a high degree of consistent integrity in keeping their commitments that they should simply let their “yes” remain “yes” and their “no” remain “no” (James 5:12).

Now, applying this general principle of faithfulness to commitments to our local churches, we turn to the expectation of all members of the local body of believers described in 1 Corinthians 3:10–17. Don’t miss the context here! Paul is addressing the local church in Corinth, marred as it was with sin, divisions, and conflict. Nevertheless, he recounted how Paul himself had planted that church, followed by Apollos, who “watered” the plant (1 Cor. 3:6). Paul then likens the body of believers in Corinth to “God’s building” (3:9). As a master builder, Paul laid the foundation of the church in Corinth, the Gospel of Jesus Christ (3:10). After he moved on, others were left behind to continue building up that local body upon that original foundation (3:10–11).

In this context of building up the local body of believers in Corinth, Paul warns that each member must “take care how he builds upon” the foundation (3:10). That is, as individual members of our local church, we are to exercise our gifts to the edification of each other (1 Cor. 12–14). In this sense we can build with either precious, strong, high-quality materials that endure or with poor, weak, low-quality materials that crumble (3:12). Obviously the good quality work in the church will lead to positively building up our brothers and sisters in Christ while low quality work will lead to the church’s deterioration and ultimate destruction. The former will be rewarded, that latter punished (3:13–15). In fact, Paul closes his building analogy for the church in Corinth by likening them to a holy temple: “Do you not know that you [the Greek is plural] are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you? If anyone destroys God’s temple, God will destroy him. For God’s temple is holy, and you are that temple” (3:16–17). We must not lose sight of the context here. The “temple” Paul refers to in this passage is neither the universal church nor the individual believer’s body. The temple is the local church in Corinth, the body of believers exhorted to work together to build each other up in the faith.

What does this text teach regarding the seriousness of keeping our commitment to our local church? First, we are to be positively exercising our gifts as well as expending our time, resources, and skills for the building of that holy temple—our local church body in which we are vital members. This is spelled out for us explicitly in 1 Corinthians 12–14. No member of the body can excuse itself from building up the local church.

Second, to either withhold our gifts or to withdraw ourselves from the local body of believers will bring destruction upon the church. If we contribute poor quality to our local church or if we fail to contribute at all, we will fail to build up the body of Christ. Instead, we will contribute to its weakening and ultimately its destruction.

Third, God will destroy those who destroy His local church. In one of the most sobering warnings of the Bible Paul says, “If anyone destroys God’s temple, God will destroy him” (1 Cor. 3:17). Think about this in relationship to our commitment to our local church. If I withdraw my time, talents, and treasures from the congregation to which I have obligated myself through membership, I will be directly contributing to its weakening and destruction. On what basis, then, can I expect to avoid the disciplining hand of God? Remember, Paul’s stern warning relates to an individual contributing to the destruction of the local church in Corinth, not to his general behavior as a Christian.

Clearly, breaking our membership commitment to a local church and the brothers and sisters of Christ with whom we have entered into a covenant relationship is serious business. So serious, in fact, that behavior leading to the destruction of the local church will mean “destruction” from the hand of God. These are not my words or my warnings, but the clear teaching of Scripture.

Conclusion

The Bible is clear about formally joining a church community by entering into a covenant commitment to a specific local body. This community then becomes our “spiritual family.” We ought to have extended family relationship with other local churches and other believers outside our local church. This is biblical and healthy. However, our “nuclear family” is the local church in which we have covenanted to build each other up in the faith, to submit to the leadership, and to love and support through good times and bad. Once we have entered into that covenant commitment, we are expected to contribute to the church’s positive growth, building it up with quality work rather than contributing to its destruction.

God is serious about the local church and our committed participation in its life and ministries. We need to strive to be just as serious in our covenant commitment to our local family of God.

In our culture of competing churches, lackluster commitments, and consumer-driven spirituality, the idea of local church membership has suffered greatly. The classic biblical concept of a family’s covenant commitment to a definable body of believers under ordained leadership with a common calling and mutual concern has consequently been treated with skepticism, disbelief, or even contempt. This kind of cavalier treatment of the local church reflects the low commitments we see throughout our culture as marriage vows are shattered, contracts are breached, and promises are broken. However, just as Christians are called to affirm their marriage vows, fulfill their contracts, and keep their promises, we are also expected to fulfill the covenant commitment we make when we publicly join in membership to a local church.

In our culture of competing churches, lackluster commitments, and consumer-driven spirituality, the idea of local church membership has suffered greatly. The classic biblical concept of a family’s covenant commitment to a definable body of believers under ordained leadership with a common calling and mutual concern has consequently been treated with skepticism, disbelief, or even contempt. This kind of cavalier treatment of the local church reflects the low commitments we see throughout our culture as marriage vows are shattered, contracts are breached, and promises are broken. However, just as Christians are called to affirm their marriage vows, fulfill their contracts, and keep their promises, we are also expected to fulfill the covenant commitment we make when we publicly join in membership to a local church.

in your second-to-the-last paragraph, you say that members covenant to “submit to the leadership.”

would love to hear from you regarding what “the leadership” means in a local church setting, and from what passage(s) “to submit” come(s).

have ordered “retro christianity.” maybe my questions will be answered in the text.

marty

What are the ideal components of a Membership Covenant? Clearly, the minimum one should consider is, “to build each other up in the faith, to submit to the leadership, and to love and support through good times and bad. Once we have entered into that covenant commitment, we are expected to contribute to the church’s positive growth, building it up with quality work rather than contributing to its destruction.” What other elements should be included, and is there suggested language for such a Covenant?