Small single-service churches . . . home churches with rotating locations . . . mega-churches with thousands of seats . . . large churches with home groups . . . mega-churches with multi-services at different times and days . . . multi-site churches with recorded messages and online campuses . . . multi-site churches with live feed from the main campus . . . multi-service churches with rotating preachers . . . single-service churches with rotating preachers . . .

Small single-service churches . . . home churches with rotating locations . . . mega-churches with thousands of seats . . . large churches with home groups . . . mega-churches with multi-services at different times and days . . . multi-site churches with recorded messages and online campuses . . . multi-site churches with live feed from the main campus . . . multi-service churches with rotating preachers . . . single-service churches with rotating preachers . . .

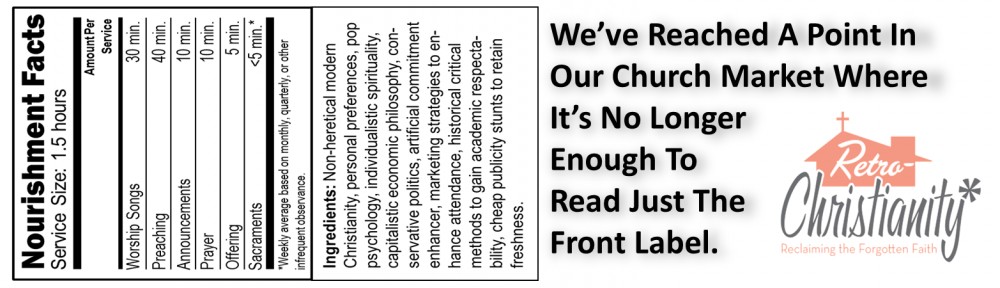

When it comes to American church ministry models, if you can imagine it, it exists.

In RetroChristianity, I describe six essential building blocks of a local church: orthodoxy, order, and ordinances as the essential marks of a local church, and evangelism, edification, and exaltation as its essential works. I also present a biblically, theologically, and historically-informed ideal worship model as pulpit/altar-centered—the effective proclamation of the Word (pulpit) and the effectual consecration of the worshipper (altar), centered on Christ’s person and work, and bounded by the Trinitarian creation-redemption narrative. The former includes reading of Scripture (1 Tim. 4:13), instructional music (Col. 3:16), and other forms of proclamation; the latter involves confession of sin (Jas. 5:16), prayers (1 Tim. 2:1), responsive music (Eph. 5:19–20), offerings (1 Cor. 16:2), and the communion meal (1 Cor. 11:20). The first is embodied in the leader’s sermon; the second is incarnated in the Lord’s Supper.

But how does a missionary or church planter move from the ideal to the real in a particular cultural context? Or how does an existing church move from the real to the ideal without a major upheaval? If given the opportunity for modifying the ministry model of your church, in which direction should you lead it? When evaluating your church’s ministry emphases and general direction either in setting short-term ministry priorities or casting a long-term vision, how do you critique your current trajectory?

In an attempt to think through these questions more carefully and to provide a frame of reference for discussion, I have established a spectrum reflecting a range of ministry models. Each model poses unique opportunities and challenges when it comes to living out the marks and works of the church as well as emphasizing a pulpit/altar-centered worship. (For a presentation and defense of these ecclesiological models, see RetroChristianity chapters 8, 9, and 10.) So, let me briefly describe these seven models. Within (and probably between) these models we can imagine numerous shades, nuances, and varieties, but I believe these seven serve as sufficient (though not perfect) “types” of modern evangelical church ministries for the sake of discussion.

Model 1: The Small Community. Small, intimate, manageable community with qualified personal pastoral presence for discipleship, accountability, and encouragement. To maintain intimacy and manageability, a single-meeting community desires to remain small—between 100 and 250 people. Among this community, the pastoral leadership strives to maintain direct relationships with church members. The pastor and elders know their flock well, understand their strengths and weaknesses, and are attuned to their needs. This incarnational presence among the community makes discipleship more intuitive and natural rather mechanical and programmatic. Accountability is a natural part of a covenanted life together. And encouragement toward faithfulness emanates from both the pulpit and interpersonal relationships. The small community model may often function as part of a larger mother-daughter network model (Model 2) or even as well-ordered, intentional smaller groups within a larger church model (Models 4, 5, and 6). And it does not preclude the possibility of denominational or inter-ecclesial associations to cooperate and pool resources for larger-scale projects.

I believe that pulpit proclamation can be more intimately and effectively crafted for a smaller group known personally by the preaching pastor. This intimacy and efficacy is easily lost when a large audience (or especially a non-present audience) is preached at from a stage or behind a camera without a personal relationship between the pastor and the congregation. I also believe it is self-evident that a full-bodied, efficacious Lord’s Supper is best observed in a single smaller community. Such an intimate observance can easily include all (not just a few) of the elements that should center about the Table—the confession of sins to one another, prayer for one another, material and spiritual support for one another, individual and corporate consecration, covenant renewal, corporate discipline, and a solemn community participation in the bread and wine as a mark of unity and means of spiritual blessing. As the crowd gathering around the altar grows, so will the tendency to emphasize one aspect of the multi-faceted eucharistic worship over other aspects. The altar will inevitably lose its significance, intimacy, and efficacy as a means of sanctification.

This small community of 100-250, however, can have its challenges. If a medium congregation (Model 3) or larger church (Model 4) shrinks in size to a smaller community, it can be difficult to the numerically declining church to adjust to a new ministry model. Members will often have a hard time adjusting to a more intimate fellowship and more volunteer-driven ministry. Also, small communities without some relationship to other local churches will often find they lack the critical mass of people necessary to carry out certain types of ministry, often leading to burn-out or weariness by volunteers. Also, a very small church can be marred by a lack of energy and excitement that can stimulate worship and service and motivate outreach and evangelism. This can be especially true when such small communities are in a larger metropolitan area. These challenges are less severe when such churches are part of suburban or rural community.

Model 2: The Mother-Daughter Network. Small to medium churches in a network with qualified on-site pastoral presence in each local church plant. Many growing churches have made the conscious decision to cap the numerical growth of a local church by strategically planting smaller “daughter” churches as evangelism and discipleship begin to cause membership in the church to increase and sprawl. Rather than treating all small groups as interdependent communities under the umbrella of a larger local body, smaller groups serve as seed groups for future church plants. The goal is not to maintain financial and organizational control and oversight (though this is a necessary stage in the cultivation of the daughter church). Rather, the goal is to establish a fully-functioning, self-sustaining small community bearing in itself all of the essential marks and works of a local church. In this case a pulpit/altar-centered worship can be easily maintained in all of its intimacy and efficacy. Usually the daughter churches maintain some kind of formal or informal association with the mother church, and they also usually cooperate with sister churches in the city or region even if there is no denominational structure enforcing such inter-church fellowship.

It should be noted that as larger churches move toward planting daughter churches, they may temporarily pass through Models 3-6 toward that goal. Many daughter churches begin as branch campuses of a multi-site church, with the intention of eventually establishing the site as an autonomous (though not independent) congregation with its own pastoral leadership, pulpit ministry, etc. The difference between a small group in a mega-church or a campus of a multi-site church on the one hand and a daughter church in association with a mother church and its various siblings is whether the congregation has its own local pastoral leadership distinct from the mother church and its own pulpit/preaching ministry.

Of course, the mother-daughter church network presupposes a trajectory of numerical growth from the small community toward a medium-to-large community. Such sustainable growth is not always possible in small towns or rural communities. Also, a mother-daughter church planting strategy requires intentional leadership training over the course of several years. Often numerical growth for churches takes place too quickly to effectively plan and execute the movement from Model 1 to Model 2. Thus, many growing churches understandably choose to (or are forced to) embrace Model 3 instead.

Model 3: The Medium Congregation. Medium congregation of smaller groups with pastoral personnel among the groups for discipleship, accountability, and encouragement. By “medium” I mean churches between 300 and 1000 people. Of course, the larger the church community, the more difficult it is to maintain a meaningfully intimate fellowship of the entire church membership (though intimate relationships can occur in smaller segments of the church’s membership) . While organizational and financial unity can be maintained, intimate community and mutuality among members must take place in subsets of the larger body. The smaller groups within a church variously manifest themselves as home groups, Sunday school classes, fellowship groups, or discipleship groups. A healthy ideal medium congregation strives to be a church of small groups, not a church with small groups. In other words, church membership implies smaller group membership. These smaller groups, then, each under qualified pastoral leadership, carry out the basic functions of the “small church” (Model 1). A generally healthy pulpit/altar-centered worship of the entire congregation can still be maintained, but often at the cost of its intimacy and efficacy, especially with regard to a loss of the Table’s multi-faceted function and significance.

Model 4: The Larger Church. Large multi-service church with voluntary opportunities for intimate community among smaller flocks under qualified pastoral leadership. The challenges toward whole church unity, intimacy, and authenticity that begin to surface in the medium congregation grow more acute in the larger church of between 1000 and 2000 members. Eventually a decision must be made to either build a larger facility or hold two or more services. Planting daughter churches as in Model 2 is usually not part of the larger church’s strategy (though such decisions can still be made). A move from personal pastoral presence to professional executive leadership occurs when trained, ordained leaders usually become disconnected from the congregation. This distancing is not intentional, but accidental. There are simply limits to how many close relationships can be maintained in very large organizations.

In some of the less ideal iterations of the larger church model, actual personal pastoral care is often delegated to lay leaders who may or may not have adequate biblical, theological, and historical training. The pulpit/altar-centered worship suffers under this kind of leadership model as messages may become detached from close relationships with the people and as members of the congregation are distanced from each other. For all practical purposes, multiple services begin to function as distinct congregations. Pastoral presence and intimacy decline, and the Table no longer functions as the obvious point of unity. In some cases, bureaucracy, personnel issues, budget concerns, and facility issues take a considerable amount of time, energy, and especially finances. As such, the direction in which a church decides to move at this stage—either upward toward Model 1 or downward toward Model 7—will often determine the church’s virtually inevitable trajectory.

However, larger churches can manage their growth well when they intentionally foster smaller groups within the larger church body, providing such groups are led by trained (and preferably ordained) qualified pastoral leaders. In such small groups, discipleship, accountability, care, outreach, and other works of the church would take place in ways similar to Model 1. Also, some larger churches may choose to attend to the ordinances in these smaller groups to allow for a more meaningful and frequent observance of baptism and especially the Lord’s Supper. However, all of this requires maximal intentionality and the prioritizing of on-going leadership development and training.

Model 5: The Mega-Church. Large auditorium multi-service campus with opportunities for programmed events and voluntary flocks led by less-qualified lay leaders. The “mega-church” is more of a mentality and methodology than a matter of head-count. However, the financial and facilities resources necessary to maintain the programming usually require at least 2000 people—often many more.

In less ideal versions of the mega-church, the model is sustained by shaping its ministries around an attractional methodology—“If we build it, they will come.” The growth strategy is usually epic—“If too many come, we build bigger.” Those who initially attend a mega-church ministry are often drawn to specific aspects of the church—youth, singles, marrieds, discipleship, worship, special programs, contemporary atmosphere, a well-known pastor, etc. All of these various elements must therefore be maintained to sustain high attendance, which must be sustained to support the high cost of maintaining the various ministry elements. An inescapable circle can develop from which there is no easy escape. Church members may become more deeply assimilated into the life of the church usually through affinity groups, which are joined voluntarily. As such, intersecting circles of social fellowship develop, and these fellowships are almost never structured around a pulpit/altar-centered ministry. Also, this model allows for many attenders or members of the church to be practically severed from discipleship and accountability. For practical purposes, many flourishing mega-churches often find themselves forced to make moves toward the multi-site church (Model 6).

Positively, mega-churches provide excellent opportunities for entry and assimilation. They naturally maintain an energetic atmosphere appealing to people of every generation. Also, as in Models 3, 4, and 5, effective and efficient aspects of mega-church ministries can occur in smaller groups, as long as these are under the care of well-trained, well-experienced pastoral leadership. Though it is possible to handle the large size of a mega-church in ways that do attend to the necessary marks and works of a church, this requires a great amount of intentionality and effort.

Model 6: The Multi-Site Church. Multi-site church campuses with broadcast messages from main campus, local pastoral presence, and voluntary flocks. The multi-site church should not be confused with the early planting stages of the mother-daughter church network (Model 2). In the multi-site mentality, the mother church has no real intention of actually establishing autonomous daughter churches. The sprouts are not church plants but merely branches of the same tree. The multi-site campus is usually a function of three elements: 1) a sprawling church membership scattered throughout a usually metropolitan area (as opposed to a localized community church membership drawn from a neighborhood); 2) a strong devotion and dedication to a well-known, well-loved preacher whose messages become the basis for unity between various campuses; and 3) a willingness to simulcast preaching from the main church or play recorded messages from the preacher as the sole or primary pulpit ministry. One practical motivation for the multi-site campus model may be an unmanageable exponential growth within the mega-church model to the degree that a single location simply cannot sustain multiple services nor accommodate traffic. However, this model can lead to a kind of “branding” in which each branch campus functions as a “franchise.” In my opinion (and in many churches’ experiences), ultimately the multi-site campus approach exacerbates unaddressed problems already inherent in the mega-church model, in which the pulpit becomes increasingly detached from a relationship with the congregation, rendering a generic “message” able to be broadcast to anybody rather than a message crafted for the focused edification of a specific body of believers. It also makes accountability, discipline, and especially a frequent and full-bodied observance of the Lord’s Supper as “one body” less practical, though not impossible. In short, a pulpit/altar-centered worship is not easily maintained in a multi-site worship. To do so requires maximum intentionality and effort.

Since originally writing this essay, I have had many opportunities to engage with leaders of multi-site churches. It seems that some have achieved a kind of balanced approach in which the individual satellite campuses function somewhat like the ministries of Models 3, 4, or 5, though without a local preaching pastor. Others have moved away from a simulcast preacher from the mother campus and have essentially become daughter churches (similar to Model 2), a model sometimes called “multi-church” rather than “multi-site church.” In the last few years we have also seen the intentional reorganizing, forced dismantling, or even scandalous implosion of several large multi-site churches. In light of both my ecclesiological critiques and practical realities observed in multi-site ministries, it is my contention that most multi-site church models are inevitably temporary arrangements that will eventually need to be reorganized. It is not a question of if the model will eventually become unsustainable, but when. This, I believe, is a reality many multi-site churches must consider in advance and prepare for responsibly.

Also, many have read my evaluations of Models 4-6 as fueled by a personal preference for smaller churches and a jealousy of successful large church ministries. This is simply not true. The fact is, even though I attend what would be regarded as a “smaller community” (Model 1), I would personally prefer a larger church and could function quite contentedly in any of the models (except Model 7). Each has its strengths and weaknesses, and each has challenges that must be carefully thought-through and addressed. The fact is, I have seen very large, mega-church ministries that do, in fact, handle their “bigness” quite well, maintaining a strong pulpit/altar-centered ministry, membership, accountability, discipleship, and the essential marks and works of the church. Sadly, however, I have seen more churches of this size neglect church membership, accountability, leadership training, and especially a proper observance of the Lord’s Supper.

Model 7: The Remote or Online Church. Self-styled “churches” encouraging remote (radio/television) or online-only experiences with no real pastoral or community presence. Before explaining why this model is unacceptable, I need to clarify that we should not confuse this model with any of the previous models that may have a radio, television, or online ministry. Model 7 is distinct in that these churches encourage the remote or online church experience as a full and sufficient relationship to the church. This is the otherwise acceptable multi-site model (Model 6) radically individualized and taken to an extreme. It completely detaches the pulpit from a real pastoral relationship with a congregation, and it utterly trivializes the biblical, theological, historical, and practical significance of the altar. Neither intimacy nor efficacy characterizes the ministry of the remote or online “church.” The marks and works of the church, if present, are not functional in any significant way. That is, orthodoxy cannot be enforced; order is non-existent; ordinances are detached from authentic community; evangelism has been reduced to a message and detached from baptismal initiation into the community; edification has been reduced to receiving information and having an emotional (or, often, financial) response; and exaltation is strictly individualistic. Though purely online-only churches are currently rare (and will hopefully remain so), many mega-churches and multi-site campus churches have incorporated online-only options into their “made to order” approach to church ministries. (For a more pointed and detailed critique of the online church movement, see my essay, “Rise of the Anti-Church: Online Virtual ‘Church.‘”)

Conclusion

Having surveyed this spectrum of church ministry models, let me make a few closing comments. My overarching question in this essay is: “Which ministry models make it easier to maintain a healthy balance of the essential marks and works of a local church and protect a meaningful pulpit/altar-centered worship?” In answer to this question, it seems the “small church” (Model 1) and “mother-daughter network” (Model 2) have the potential to more closely incarnate the ideal without having to overcome great practical and organizational challenges. The medium congregation (Model 3) is also sustainable, though in my mind it does begin to require some conscious planning and implementation. A consideration of the “larger church” (Model 4), “mega church” (Model 5), and “multi-site church” (Model 6), lead me to issue a few cautions, not so much against these models per se, but against the temptation to neglect the marks and works of the church and a pulpit/altar-centered worship simply because of the logistical and practical challenges involved. It seems to me that as one moves from Models 1 through 6, the need for wise, well-informed, intentional, and consistent attention to the marks and works increases, perhaps exponentially. Church leaders and members need to be aware of these challenges and plan accordingly.