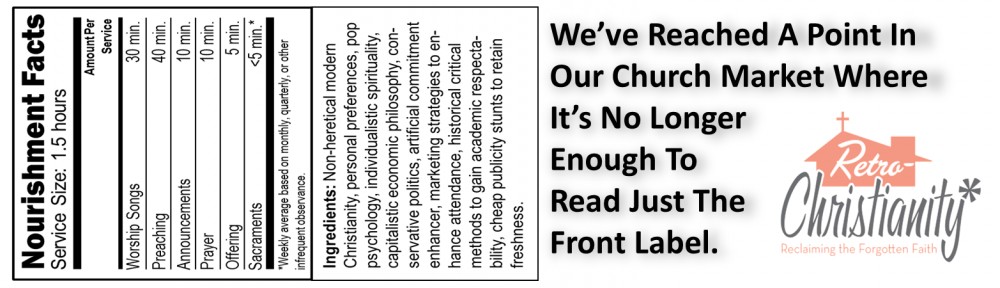

Lately I’ve been encountering Christians from both denominations and “home churches” who are meeting on Saturday (the Sabbath) to worship, rather than on Sunday. When asked why they do this, the responses are diverse. Some believe the regulation in the Ten Commandments requires the observance of the Sabbath day. Others claim that this was the day the New Testament believers and the ancient church assembled for worship, and they want to return to that original practice.

Lately I’ve been encountering Christians from both denominations and “home churches” who are meeting on Saturday (the Sabbath) to worship, rather than on Sunday. When asked why they do this, the responses are diverse. Some believe the regulation in the Ten Commandments requires the observance of the Sabbath day. Others claim that this was the day the New Testament believers and the ancient church assembled for worship, and they want to return to that original practice.

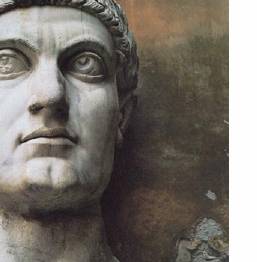

Obviously, if the earliest Jewish believers (that is, the apostles and their first and second-generation converts) worshipped on Saturday, somewhere along the way the Christians changed from Saturday to Sunday. In fact, in The Da Vinci Code, this was one of the charges the dreadful fictional historian laid at the feet of Emperor Constantine and the “paganizing” of Christianity. He claimed that the earliest Christians worshipped on Saturday, but that when Christianity “sold out” to the world, they started worshipping on Sunday, the day the Roman and Greek pagans worshipped the sun.

Because this question comes up all too frequently, I wanted to debunk the myths and set things straight as a historian who actually knows what really happened. And unlike many biblical and historical issues, this matter is an open-and-shut case. The historical evidence is clear.

The Bible says the earliest Christians gathered together on “the Lord’s Day.” By AD 95, the phrase “the Lord’s Day” (Greek kuriake hemera) had apparently become a common term for the day of Christian corporate worship centered on preaching and the Lord’s Supper (called the “eucharist” or “thanksgiving”). We see that the Apostle John so used it in Revelation 1:10, assuming his readers in western Asia Minor would know immediately what he meant by “the Lord’s Day.”

Prior to that, the apostles referred to Sunday as “the first of the week,” on which Christ rose from the dead (Matthew 28:1; Mark 16:2, 9; Luke 24:1; John 20:1). Jews at the time regarded Saturday (the Sabbath) as the seventh or “last” day of the week.

We see indications already in the earliest days of the church that the apostles and their disciples gathered together for worship on the “first day of the week,” that is, Sunday, in commemoration of the resurrection of the Lord Jesus Christ. In Acts 20:7, we read: “And upon the first day of the week, when the disciples came together to break bread, Paul preached unto them, ready to depart on the morrow; and continued his speech until midnight” (KJV). The practice of “breaking bread” is an early reference to the corporate worship of the believers, centered on the Lord’s Supper and fellowship around the preached Word. We also see Paul addressing the issue of the collection of money for the churches in 1 Corinthians 16:1–2, instructing the Corinthians to make the collection “upon the first day of the week” (16:2). Because this was a collection from among members of the church, it indicates that this was the day they gathered together as a corporate body.

Now, we do know that on the Sabbath the apostles would go to the Jewish synagogues and preach about Christ to the Jews and God-fearing Gentiles. This is absolutely clear (Acts 13:14; 13:42; 13:44; 16:33). But this evangelism is not the same as gathering together for the apostles’ teaching, the breaking of bread, and prayer—characteristics of early Christian worship.

So, from the New Testament we see that there’s an early emphasis on Sunday, the “Lord’s Day,” the day the Lord rose from the dead, also called the “first of the week.” When we move forward in church history to the very next generation of Christians—to people who actually sat under the teachings of the apostles and their disciples themselves—the picture becomes even more clear.

In Didache 14.1, a church manual which, according to an emerging consensus of specialists, was probably written in Antioch in stages between AD 50 and 70, the instruction is simply, “And on the Lord’s own day gather yourselves together and break bread and give thanks.” The “Lord’s own day” is the same phrase used in Revelation 1:10 by John.

At about the same time (around A.D. 80 or so), an anonymous but highly-respected letter later attributed to “Barnabas” makes it clear that Christians intentionally worshipped not on the “seventh day” (the Sabbath), but on the “eighth day,” as a memorial of the resurrection:

Further, He says to them, “Your new moons and your Sabbath I cannot endure.” Ye perceive how He speaks: Your present Sabbaths are not acceptable to Me, but that which I have made, namely this, when, giving rest to all things, I shall make a beginning of the eighth day, that is, a beginning of another world. Wherefore, also, we keep the eighth day with joyfulness, the day also on which Jesus rose again from the dead. And when He had manifested Himself, He ascended into the heavens. (Barnabas 15.8)

This evidence is important, because it comes to us from a very early and respected Christian document that helps us understand historically when the earliest Christians worshipped. It was the “eighth day” of the week, the day Jesus rose from the dead: Sunday. Clearly th

Around AD 110, Ignatius, the pastor of Antioch, wrote a letter to the church in Magnesia of Asia Minor while on his way to martyrdom in Rome. In that letter he addressed the problem of Judaizers infecting the church with divisions and false doctrine, and found himself having to explain the Christian practice of worshipping on Sunday rather than on the Sabbath:

If, therefore, those who were brought up in the ancient order of things [Judaism] have come to the possession of a new hope [Christianity], no longer observing the Sabbath, but living in the observance of the Lord’s Day, on which also our life has sprung up again by Him and by His death—whom some deny, by which mystery we have obtained faith, and therefore endure, that we may be found the disciples of Jesus Christ, our only Master . . . (Ignatius, To the Magnesians 9.1)

Before you dismiss this evidence as “outside the Bible” and a later corruption by the church fathers, remember that Ignatius was not just some monk from the Dark Ages. He was an old man already by AD 110, which means he was middle aged when the apostles themselves still lived and as pastor of Antioch would have known some of them. Further, history tells us that he was close friends with Polycarp, pastor of Smyrna, who was himself ordained into the pastoral office by the apostle John himself. So, the teaching about Sunday worship by Ignatius almost certainly came from the apostles and their disciples, whom Ignatius knew. Furthermore, note that Ignatius was not pushing for a new day of worship, nor was he defending it. Rather, he was simply explaining why the original Jewish disciples of Jesus switched from keeping the Sabbath to worshipping on Sunday, the Lord’s Day, the day of His resurrection.

The biblical and historical facts are clear: every bit of evidence we have shows that from the apostles themselves throughout the early church up until this very day, the true church met together for worship on the Lord’s Day, the first day of the week, the day after the Sabbath, Sunday. On this day they commemorated week after week the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Therefore, any teachers or traditions today that seek to establish Sabbath observance or corporate Christian worship on Saturday are not in keeping with the apostolic practice or the most ancient practice of the church, but are, in fact, deviating from the teachings of the apostles.

But what about Emperor Constantine in the fourth century? Didn’t he make Christianity the official Imperial religion, establish the State Church, and change Christian worship to Sunday? No! First, Constantine legalized Christianity (which had previously been outlawed). He did not make it the official state religion (that came later by future emperors). Second, his program of funding the construction of church buildings and the copying of Scripture was to replace the buildings and Bibles that had been destroyed or burned in the last great persecution. Those acts of Constantine were matters of restitution for wrongs inflicted on the church. Third, with regard to Sunday worship, Constantine simply decreed that Christians would be allowed to take Sunday mornings off for worship, making room in the laws for Christians to observe legally what they had already been observing illegally, that is, Sunday morning worship. Constantine did not, in fact, change Saturday to Sunday worship. (This myth, by the way, has been thoroughly debunked by patristic scholars, and I have recently attended meetings of patristic experts who were amazed that anybody would still allege such an indefensible version of history.)

Let’s briefly return to the reasons I’m often given for changing Christian worship to Saturday. 1) “Because the regulation in the Ten Commandments requires the observance of the Sabbath day.” If this were true, then the apostles and their original disciples themselves broke the Sabbath and set a bad precedence. This is unacceptable. 2) “The Sabbath was the day the New Testament believers and the most ancient Christian church assembled for worship.” This is simply not true and there is no evidence that it ever was. Those who maintain this claim are guilty of revisionist history.

Fact: from the days of the apostles themselves Christians have celebrated the resurrection of Jesus on Sunday. So, let’s stop this nonsense about “ancient Saturday worship” and put the Sabbath to rest.