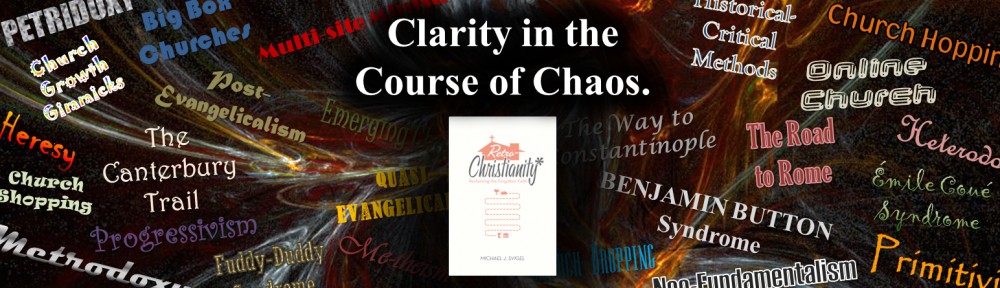

Naming an idea can be risky. The newly-named “idea” takes on a life of its own and can then be accepted, rejected, modified, ignored, loved, or despised. Nevertheless, I’ve decided to finally name that cluster of ideas that has been gestating for some years now—about fifteen, to be precise. I actually think the child was born a few years ago, but he’s been awaiting an identity—something that will distinguish him from his look-alike siblings that came before him. So, the name I’ve given my course of thinking is RetroChristianity. I will explain exactly what this means and why I chose this particular name in due time. But to do this successfully, I first need to name and describe a few other concepts in contemporary Christian thinking. These terms include “Orthodoxy,” “Heterodoxy,” and “Heresy.” To these common labels I want to add two more: “Metrodoxy” and “Petridoxy.”

Naming an idea can be risky. The newly-named “idea” takes on a life of its own and can then be accepted, rejected, modified, ignored, loved, or despised. Nevertheless, I’ve decided to finally name that cluster of ideas that has been gestating for some years now—about fifteen, to be precise. I actually think the child was born a few years ago, but he’s been awaiting an identity—something that will distinguish him from his look-alike siblings that came before him. So, the name I’ve given my course of thinking is RetroChristianity. I will explain exactly what this means and why I chose this particular name in due time. But to do this successfully, I first need to name and describe a few other concepts in contemporary Christian thinking. These terms include “Orthodoxy,” “Heterodoxy,” and “Heresy.” To these common labels I want to add two more: “Metrodoxy” and “Petridoxy.”

By “Orthodoxy” I signify the correct view on the central truths of the Christian faith and a proper practice of Christian works. As a rule of thumb, orthodoxy is that which has been believed and practiced everywhere, always, and by all. The “all” includes those who people who intend to be counted among orthodox Christians and who have generally been regarded as such by other orthodox Christians. Orthodoxy means holding the right opinion about crucial Christian truths and acts in keeping with what Christianity has always believed about these things. Some things that fit this general criteria are: 1) God created all things out of nothing; 2) God is Triune: one divine essence in three Persons—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit; 3) The eternal Son of God became incarnate through the Virgin Mary and was born Jesus Christ, fully God and fully human, two distinct natures in one unique Person; 4) Jesus Christ died to pay for our sins, rose from the dead victorious, and ascended into heaven, waiting to return from heaven to earth to act as Judge and King; 5) The Holy Spirit moved the prophets and apostles to compose the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments, the inspired, unerring norm for the Christian faith; 6) The Church is Christ’s body of redeemed, baptized saints who by faith partake of the life and communion with God through Jesus Christ in the new community of the Spirit. Some universal practices have included baptism as the rite of initiation, the Lord’s Supper (or communion, or eucharist) as the rite of continued fellowship, evangelism, missions, charity, worship, and Bible teaching. Many other things have been taught and practiced everywhere, always, and by all, but this sample list indicates the kind of central, crucial doctrines that mark one as “orthodox.”

Now this all sounds simpler than it actually is. Sometimes it requires a little bit of squinting in order to overlook minor blemishes on an otherwise hopeful history of orthodoxy. The reality is that without constant check-ups and regular cleaning, orthodoxy is subject to “truth decay.” This can happen to individuals, to churches, to vast communities, to entire generations. But don’t despair! One of the main functions of the Spirit of Truth is to guide the church into truth, to restore her to orthodoxy when she veers too far, and to breathe into her renewed vitality. The history of the church is filled with these revival movements that retrieve forgotten aspects of orthodoxy. So orthodoxy can never be taken for granted. It must be constantly re-received and re-taught. It is not passed down from one generation to another in the form of a creed or confession if that creed or confession is not faithfully and intentionally taught. Orthodoxy is not bestowed upon the next generation through the Bible if the Bible is not read and explained within the context of classic orthodoxy. There’s no such thing as orthodoxy by osmosis or trickle-down orthodoxy. It must be intentionally and clearly taught everywhere, at all times, and to all.

Moving on, I use the term “Heterodoxy” to mean, literally, “another opinion.” Heterodox teachings tend toward the margins of the received doctrines of the faith. And they sometimes teeter at the very edge. They still want to be part of the Christian tradition and still acknowledge the central Christian truths, but they also want to be unique, innovative, and clever in their theology and practice. They feel comfortable recasting traditional truths in nontraditional language. They sometimes want to rearrange, reinvent, reinvigorate, and reformulate the things that had been handed down to them. They like to surf the waves of the margins, buck the system, go against the grain—all within the community of orthodoxy. However, heterodoxy often results in an unintentional distancing from the normative center of Christian orthodoxy . . . and with a little push heterodox teachers run the risk of breaking free from orthodoxy’s gravitational pull and winding up in the bleak void of heresy. Heterodoxy is also often characterized by exaggerating a minor distinctive and trying to jam it into the center of orthodoxy. When a unique aspect of a person’s theology becomes the focal point, the true center of orthodoxy becomes marginalized and minimized. Thus, heterodoxy develops because of a failure to keep the primary orthodox truths front and center. Division, dissension, and destruction often ensue. Heterodoxy is cured by intentionally and clearly teaching orthodoxy everywhere, at all times, and to all.

I use the term “Heresy” to describe doctrine that challenges and destroys the central core of orthodoxy. As such, heresy alone is damnable doctrine. It often finds its origins as a radical heterodoxy, but not all heterodoxy ends up in denying basic fundamentals of the Christian faith. Heresy differs from heterodoxy in that the heretic knowingly (not ignorantly), willfully (not accidentally), and persistently (not momentarily) denies a key tenet of historic orthodox Christianity. He or she rejects certain truths that have been believed everywhere, always, and by all. For example, somebody who denies the full deity and humanity of Christ is a heretic. The belief that Jesus of Nazareth did not literally rise from the dead is heretical. And the view that the Holy Spirit is a created being and not a fully divine person is heresy. Heresy is defeated by intentionally and clearly teaching orthodoxy everywhere, at all times, and to all.

Orthodoxy. Heterodoxy. Heresy. I think these categories are clear. Now, floating among Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy I see two tendencies, especially in free church evangelicalism. I call these tendencies “Metrodoxy” and “Petridoxy.”

“Metrodoxy” is a term I coined to describe trendy, faddish, and “cool” doctrines and practices that tend to take over contemporary churches, especially “megachurches” and megachurch wannabes. If you want your church to have greater cultural “impact,” to draw media attention, and to place itself on the map of evangelical Christianity, you must accept and live by metrodox values. These include relationship, not religion . . . contemporary, not conventional . . . relevance, not ritual . . . innovative, not obsolete . . . fresh, not stale. Metrodoxy thrives in metropolitan areas, drawing from a pool of young, energetic men and women who have excess time and money. This group is often impressed by a clever lingo, advanced technology, and trendy buzz. Anything perceived as boring, belabored, or bogged down gets snuffed. But amidst the excitement, metrodox churches tend to be in a constant state of identity crisis, needing to reinvent or re-brand themselves every few years. After a few phoenix-like rebirths, these churches eventually find themselves adrift, unsure of what they’re supposed to be doing or why. Of course, we find all sorts of ready captains prepared to take over and steer the ship toward some new and trendy port . . . but these navigators are usually not going back to classic orthodox beliefs and practices as their guides to lead them on. The result of this constant identity crisis is often a failure to identify and pass on what has been believed and practiced everywhere, always, and by all. So, extreme metrodoxy can be treated by intentionally and clearly teaching orthodoxy everywhere, at all times, and to all.

On the other extreme we find what I call “Petridoxy.” If the metrodox are too progressive and trendy, the petridox are frozen in time, unable and unwilling to change. They have been petrified. They tend to fear change as a great evil, not realizing that their own practices were themselves once quite new (and likely controversial). They often have a very myopic perspective on their own history, believing their way has stood the test of time. They have no desire to critically examine their narrow perception of so-called “orthodoxy” or to evaluate whether what they’re doing actually does help to preserve and promote central orthodox beliefs and practices. Petridox churches would just as soon die a slow and painful death than make major adjustments. Having lost sight of the fundamental goal of receiving, preserving, and passing on the faith once for all entrusted to the saints, petridoxy settles on one method of receiving, one manner of preserving, and one means of passing on the faith . . . and then it congeals in that particular form. Petridoxy therefore tends to be primitivistic, reactionary, ultra-conservative, and idealistically nostalgic. However, petridoxy can be softened by refocusing attention on the purpose of the church’s forms and structures: to intentionally and clearly teach orthodoxy everywhere, at all times, and to all.

With this background on concepts of orthodoxy, heterodoxy, heresy, metrodoxy, and petridoxy, I’m ready to explain the concept of “RetroChristianity.” The prefix “retro” means “involving, relating to, or reminiscent of things past.” But in contemporary compound words, it indicates an attempt to bring the things of the past into the present, giving both the past and the present a new life.

First let me make it perfectly clear that RetroChristianity is not fundamentalism redivivus, a retreat back to Papal Rome, a pilgrimage to Eastern Orthodoxy, or a veiled attempt to promote a flaccid ecumenical faith. Rather it’s an honest attempt to more carefully navigate our received orthodox faith and practice through the precarious channel between metrodoxy and petridoxy, both of which can shipwreck the faith. Therefore, RetroChristianity wants to bridge the gap between the ancient and contemporary church without going to two extremes: 1) idealizing the ancient and condemning the modern, or 2) eschewing the ancient and seizing the contemporary. RetroChristianity has some things in common with the many “ancient-future” movements, while acknowledging that many forms of that trend can easily slip into just a new identity for metrodox churches . . . or drive headlong into the rocks of an out-of-touch primitivistic petridoxy. RetroChristianity tries to address the real practical questions of “how” we can intentionally and clearly teach orthodoxy everywhere, at all times, and to all. It also draws much of its inspiration from the concept of paleo-orthodoxy and thus explores the foundational work of the patristic period. But it also seeks to move, in concrete practical steps, from that pre-modern, pre-Christian cultural context to our post-modern, post-Christian context.

Ultimately RetroChristianity means carrying on a constant dialogue with the past, but it also requires an actual practical connection with the present and an orientation toward the future. Therefore, it asks how we can and ought to teach and practice orthodoxy everywhere (that is, in every kind of church and ministry around the world), always (in every ministry opportunity, outreach, or service), and to all (young and old, rich and poor, educated and uneducated, men and women). RetroChristianity demands that the past first be reckoned with on its own terms. It can not settle for picking over the past for relevant bits and pieces that will make us feel more “connected” to our roots. It can’t stand for politely consulting the ancient Christians to make us look sophisticated. And it can’t naively transplant the past into the present as if the preceding centuries of development never happened. As such, the dialogue is a complex, time-consuming, strenuous work that requires the input of many. This includes patristic, medieval, and reformation scholars; pastors, teachers, and laypeople; denominational and free churches, and numerous others interested in genuinely engaging in either real transformation . . . or unashamed preservation.