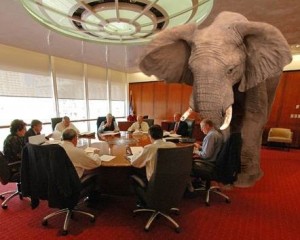

“The elephant in the room” is an English idiom that refers to a problem obvious to everybody . . . but avoided by most because addressing it would cause discomfort or embarrassment. In a marriage relationship, the elephant in the room might be intrusive in-laws . . . or a husband’s perpetual under-employment. In a business it might be an unprofitable product line . . . or a problem employee the boss can’t seem bring herself to fire. In a church the elephant might be a certain ineffective ministry program that drains money and time . . . or a doctrinal issue that could cause major upheaval if brought up at the next elder’s meeting.

“The elephant in the room” is an English idiom that refers to a problem obvious to everybody . . . but avoided by most because addressing it would cause discomfort or embarrassment. In a marriage relationship, the elephant in the room might be intrusive in-laws . . . or a husband’s perpetual under-employment. In a business it might be an unprofitable product line . . . or a problem employee the boss can’t seem bring herself to fire. In a church the elephant might be a certain ineffective ministry program that drains money and time . . . or a doctrinal issue that could cause major upheaval if brought up at the next elder’s meeting.

When it comes to the doctrine and practice of water baptism, there are a couple “elephants in the room.” The first relates to whether baptism replaces circumcision as the rite of initiation into the community of God’s covenant people. The second regards the relationship between baptism and the forgiveness of sins. Because of the interdependence of the six facets of baptism explored in this series of essays, we have already lightly touched on these issues as we discussed other topics. However, knowing that I would eventually be dealing with these themes head-on, I intentionally avoided those two “elephants in the room.”

The first essay in this series looked at the twofold confessional nature of baptism: 1) confession of faith in the creation-redemption narrative of the triune God and 2) personal association with the atoning death and saving resurrection of Jesus Christ. The second essay examined two practical dimensions of baptism: 3) turning away from a life of sin and 4) pledging a life of holiness in following Christ. This third essay in the series will explore a final category of pairs that will fill out our doctrine and practice of water baptism from a biblical, theological, and historical perspective: the community nature and function of baptism. This category includes 5) baptism as a rite of initiation into the new covenant community and 6) baptism as a mark of official community forgiveness of sin.

Though we have danced around them in the previous essays, I’m now prepared to deal with the elephants directly in this third (though not quite final) installment.

5. Baptism as a rite of initiation into the covenant community (1 Cor. 12:13; Gal. 3:27)

The place: Jerusalem. The time: Pentecost, ten days after Christ’s ascension. The Holy Spirit has been poured out in a new and powerful way, and the church has been founded. As droves of new converts to the Christian faith pour in, they are initiated into the church. Acts 2:41–42 says, “So those who received his word were baptized, and there were added that day about three thousand souls. And they devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and the fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers.” The order closely follows Christ’s command in Matthew 28:19—“Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you.” The apostles preached the gospel. Many who heard believed and received the word in faith. In response, they were “added” by means of baptism. Added to what? To that community in which the apostles’ teaching, fellowship, breaking bread, and prayers took place. That is, they were added to the church. Acts 6:7 says that as new converts came in, “the number of disciples continued to increase,” and 9:31 says that in the same way “the church . . . continued to increase” throughout Judea and Samaria.

In keeping with the words of Jesus and the practice of the apostles, the New Testament presents water baptism as the means by which the church admitted new disciples into its membership, thus “adding to” and “increasing” its number. In fact, after examination and instruction in basic beliefs and the expected new lifestyle of Christians (see part 1 and part 2 of this series), new believers in Christ were baptized as a mark of covenant initiation into a local church community . . . and thereby also into the visible universal church, of which each particular church is a microcosm. Simply put, believers in Christ who had not received the seal of baptism were not admitted into church membership. This is why the first century manual of church order, The Didache (c. A.D. 50–70), not only instructs baptismal candidates on how to live according to Christ’s teachings, but it also includes specific instructions on how to live in the new covenant community as a faithful member: “My child, night and day remember the one who preaches God’s word to you, and honor him…. Moreover, you shall seek out daily the presence of the saints, that you may find support in their words. . . . In church you shall confess your transgressions, and you shall not approach your prayer with an evil conscience” (Didache 4.1, 2, 12). Thus, in the early church, water baptism was not only a confession of faith and a mark of repentance from sin . . . it was also the rite of initiation into the new covenant community.

In this way, Christian baptism is similar to Hebrew circumcision as the sign of entrance into membership in the covenant community. Just as circumcision was the rite of initiation into the Old Covenant community (Israel), baptism is the rite of initiation into the New Covenant community (the Church). As circumcision meant that the member of the Old Covenant community was obligated to keep the stipulations of the Old Covenant Law (Gal. 5:3), believers in Christ who submit to water baptism are obligating themselves to keep the stipulations of the teachings of Christ and the apostles (Matt. 28:19). It is an altogether different question whether the circumcision of infants in the Old Covenant was intended to transfer to the New in the form of infant baptism. The answer to this question depends on how much continuity exists between the Old and the New. Regardless of where one lands on the issue of infant baptism, the parallel between the two marks of initiation can still be maintained: circumcision for the Old and baptism for the New. Both are to be regarded as rites of initiation into the covenant community.

Both the Bible and the church throughout the centuries have viewed baptism as the outward, visible sign of initiation into the church. Church historian J. N. D. Kelly writes, “From the beginning baptism was the universally accepted rite of admission to the Church” (Early Christian Doctrines, 192). The idea of an “unbaptized Christian” is completely foreign to the Bible and the early church. I know of no credentialed scholar of early Christianity who would suggest that the early church had room for an unbaptized Christian. In fact, our accounts of conversion in the New Testament include baptism. This isn’t a matter of being legalistic. It’s a matter of obedience to the command of Christ (Matt. 28:18) and the teachings of the apostles (2 Tim. 2:2). The burden of proof is therefore on anybody who would admit an unbaptized believer into membership in the new covenant community, the church.

In the same way that a wedding ceremony functions as a public demonstration and pledge of an engaged couple to lifelong marriage, water baptism is the public celebration of our genuine devotion and commitment to Christ and His church. It’s the rite of initiation into the community of other baptized believers, the Body of Christ, and therefore it must precede church membership, observance of the Lord’s Supper, discipleship, and leadership. Baptism is a mark of covenant commitment, rendering us accountable to the church community. Just as Spirit baptism unites us spiritually to Christ and makes us members of his mystical body (1 Cor. 12:13; Eph. 2:6), so water baptism unites us physically to the visible body of Christ, the church, making us members of his covenant community. Yes, I believe Christians are mystically, spiritually, and permanently united to Christ by the Spirit at the moment they are saved by grace through faith. But this is only recognized, authenticated, and sealed by that saved believer’s entrance into visible membership with a local church.

One final word on this. Often times believers confuse the relationship between the local church and the church universal or “catholic.” They believe that the church universal is invisible, that one is a member of that church apart from any relationship with a local church. However, this is a misunderstanding of the relationship between local and universal. The church universal (“catholic” or “global”) is comprised of all local churches worldwide. It is not an invisible entity that exists apart from local manifestations of the church. So, under ideal circumstances, a new believer should be baptized under the authority of and into membership in a local church. By this act—becoming a member of a local church—he or she also is a member of the church universal, or “catholic.” When a baptized Christian transfers local church membership, he or she doesn’t need to be re-baptized for the new local church any more than a citizen of a country needs reapply for citizenship when he or she moves to another city or state.

In sum, baptism is not only a confession of our Christ-centered, Trinitarian faith and an official turning from sin to a life of holiness. It is also a rite of initiation into the new covenant community, granting the new initiate full rights and privileges of membership in the local and global body of Christ.

6. Baptism as a mark of official community forgiveness (Acts 26:18)

The Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed of A.D. 381 states, “We believe in one baptism for the forgiveness of sins.” Although the Greek text of this article of confession is identical to biblical language (with the exclusion of the prepositional phrase “of repentance”), many Protestants balk at any connection between forgiveness of sins and the practice of water baptism. Passages like Mark 1:4; Luke 3:3; Acts 2:38 become “problem passages” that must be explained . . . or they are regarded as texts that no longer apply to Christians for some reason. However, let me suggest that real forgiveness of sins is granted at the moment of water baptism—but a forgiveness that relates not to the individual’s eternal and invisible relationship with God, but to the saved believer’s relationship to the Christian community. This forgiveness extended by the authority of the Christian church affects a person’s standing with the community, allows him or her to participate in the blessings of the community, and protects the forgiven person from spiritual dangers that lay outside the protection of the community.

To understand the kind of official community forgiveness marked by the rite of baptism, let me come at this from the angle of church discipline. It’s no wonder that in a church culture that has all but abandoned a biblical practice of church membership and discipline, the idea of the church’s authority and responsibility to grant initial covenant community forgiveness through baptism has also fallen out of favor. Let me begin, then, by showing that the gathered local church does, in fact, have authority to grant and withhold official forgiveness to and from its members. Furthermore, God Himself confirms this binding and loosing by withdrawing or extending temporal forgiveness, that is, properly-administered church discipline is accompanied by divine discipline.

In 2 Corinthians 2, Paul instructed the church in Corinth to respond graciously to the repentant sinner who had suffered under the punishment of church discipline. I understand this as a reference to the person who had been officially put out of the church for sexual immorality in 1 Corinthians 5:1–13. Since that proper exercise of church discipline, the sinner had repented. Now the church was instructed to show grace and mercy toward him as a brother. He had suffered sufficient “punishment by the majority” (2 Cor. 2:6). How? They had removed him from among their membership (1 Cor. 5:2). In an official assembly of the church, in the name of Jesus Christ and with His authority, the church handed that man over to the domain of Satan “for the destruction of the flesh” (1 Cor. 5:4–5). With this authority and responsibility to exercise discipline, they judged the sinner “inside the church” by putting him outside the church, obeying the principle of Deuteronomy 13:5 to “purge the evil person from among you.”

In other words, the church had not only the responsibility and authority, but also the obligation, to hold the unrepentant sinner’s stubborn immorality against him, removing him from the church’s membership and fellowship, withholding official community forgiveness from him, and placing him once again in the dangerous realm of Satan, where he would literally stand in mortal danger. What we see happening in the process of church discipline is a suspension of the rights and privileges entered into through baptismal initiation—a reversal, so to speak, of the blessing of the baptized believer in good standing with the church.

The local church, therefore, has the authority, in the name of Jesus and by His power, to withhold temporal forgiveness from the unrepentant sinner. By this official act of righteous “unforgiveness,” the church treats the guilty sinner like “a Gentile and a tax collector,” exercising its authority to hold a person’s sin against him or her. In the context of this authority of church discipline, Jesus said, “Whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven” (see Matt. 18:18 and its context). Some suggest this authority for binding and loosing was limited only to the apostles. After all, Jesus breathed on the apostles themselves and said, “Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven them; if you withhold forgiveness from any, it is withheld” (John 20:23). However, as an apostle, Paul himself indicated that the officially gathered church, including its ordained leadership, has this same authority of disciplinary binding and loosing, unforgiving and forgiving: “Anyone whom you forgive, I also forgive” (2 Cor. 2:10). They didn’t need to wait for Paul to give the apostolic “okay” to exercise discipline and re-extend forgiveness. In fact, Paul was upset that they hadn’t taken these initiatives on their own . . . demonstrating that the authority to extend and withhold covenant community forgiveness was not merely the prerogative of the apostles, but that of the gathered local church itself.

In light of the whole teaching of the New Testament on this matter, it seems likely that the “keys of the kingdom” mentioned in Matthew 16:19 refer metaphorically to the church’s authority to guard its own gates, explaining why the same language of “binding and loosing” is found there as well. Each duly-led and constituted local church has therefore inherited the apostolic authority of binding and loosing, forgiving and withholding forgiveness—that is, the duty and responsibility for: 1) refusing admission to unbelievers or unrepentant sinners into church membership, 2) admitting believing and repentant sinners into membership, and 3) suspending membership for unrepentant believers. These metaphorical keys for guarding the gateway to the kingdom were not passed from Peter to the Popes, but equally shared by all the apostles who received the Holy Spirit (John 20:23). Nor were they limited merely to a succession of bishops or an ecclesiastical magisterium. Rather, this authority to bind and loose, forgive and withhold forgiveness, is shared today in the post-apostolic age by each local church in union with its ordained leaders, the elders, as Paul’s instructions to the church in Corinth indicate (2 Cor. 2:10). In fact, Jesus’s instruction ultimately to take matters of church discipline before the church indicates that the church itself, under its leaders (that is, gathered in an official capacity) had the authority of binding and loosing.

If church discipline, then, is the church withholding official covenant community forgiveness from a believing church member who refuses to repent, and if the church has the authority to subsequently grant forgiveness to him or her when he or she does repent by readmitting him to full fellowship, then water baptism should be seen as the church’s original mark of granting official community forgiveness to the believing, repentant sinner. Yes, it’s the believer’s individual act of repentance from a life of sin, but it’s also the church’s act of forgiveness and admission into the community. With this act of official community forgiveness through the sign of water baptism, the believer is visibly transferred from the world to the church, from the way of death to the way of life, from the kingdom of darkness to the kingdom of light. In baptism, the repentant believer turns “from darkness to light and from the power of Satan to God, that they may receive forgiveness of sin and a place among those who are sanctified by faith in” Jesus Christ (Acts 26:18). In this way we can say with Peter that water baptism “saves” us, not from hell, damnation, and divine wrath—the spiritual salvation which is by grace through faith alone—but from a destructive lifestyle of sin and from the powers of Satan and the spirits of darkness. No wonder the early church quickly associated exorcism and the breaking of the oppression of demons with the act of water baptism! By repenting from a pagan lifestyle and entering into the protection of the church, believers were being really and truly saved from the satanic realm.

Let me be clear. Though water baptism does not bring about God’s eternal forgiveness nor the baptism of the Holy Spirit, water baptism does mark—really and truly and not just metaphorically—the temporal redemption of the sinner from a lifestyle of sin and the spiritual oppression of the devil and his demons. The baptized believer, then, enjoys “a place among those who are sanctified by faith,” that is, among the church, the communion of saints (Acts 26:18).

Therefore, through official church discipline, whereby the same officially gathered church exercises its binding and loosing authority to “unforgive” or “withhold forgiveness” from a baptized believer who refuses to repent, that person is put out of the protection of the community they had entered by baptism. What was accomplished in baptism—official forgiveness—is undone by excommunication. They are now exposed to physical sickness and destruction . . . even death. Any charitable support in the form of food, drink, or financial assistance is no longer received by the stubborn transgressor. And having been cast out from under the umbrella of spiritual protection provided by the church, the unrepentant believer is again exposed to the deceptions and destruction of Satan (see, 1 Cor. 5:5; 1 Tim 1:20; and perhaps Jas. 5:14–15; 1 John 5:16–17). And as God honors what has been bound or loosed on earth by also binding and loosing in heaven, He will discipline those true believers whom He loves (Heb. 12:5–11). Upon repentance, the once-for-all baptized believer does not get re-baptized any more than a prodigal son who has been kicked out of his parent’s house needs to be adopted when he repents and comes home. Rather, he or she is to be officially “forgiven” by the church and welcomed back into fellowship and communion (2 Cor. 2:10).

There. I have dealt with the elephants in the room: baptism as initiation into the covenant community and baptism as the mark of official community forgiveness. These are probably the two most controversial and difficult teachings regarding water baptism. Most likely they will receive the closest study and scrutiny. But like the idiomatic “elephants in the room,” they can’t be ignored forever. Yes, baptism should function as the rite of initiation into the the new covenant community, just like circumcision marked the initiation into the Old Covenant communtiy. And yes, baptism should function as the church’s mark of official community forgiveness of sins for the newly-initiated member, rendering him or her a “member in good standing” with the community and access to the blessings of God that come only through the ministries of the church.

(NOTE: This series will be concluded in Part 4 of 3: “Riding the Elephant”)